French all-concrete: a long history

Largely associated with the construction of large collective housing estates, all-concrete business is mostly regarded as a direct product of post WWII’s 30-year boom era. Its story however begins during the World War as it was in fact tailored for the benefit of the German occupier, with French companies founded and developed through a juicy partnership with German companies for the building of the Atlantic Wall…

18/03/2019

Our modern society is the direct product of, mainly, the industrial revolution and both of the 20th century’s world conflicts. However, while the industrial revolution is an official part of our national history, the legacy of world wars’ structuring role in regards to modern societies is less known of a topic. Between the two wars, construction industry followed a relatively binary structural organization: small craft businesses worked for private sector and individuals, while civil engineering companies worked exclusively for the state and local authorities, building major civil and military infrastructures such as fortifications, bridges, roads, ports and dams.

The 1929 crash saw a dramatic drop in private construction volume that caused many small businesses to close. Meanwhile, companies working for the state maintained or even strengthened their volume of activity, thanks to the development of major national projects such as the Maginot Line, which was the main public procurement from 1928 onwards.

Then, in 1940, the effects of the crisis and those of the war combined and finally reached many companies, leading them to bankruptcy. As with every crisis, the number of operators in the construction sector drastically reduced and, in return, this reduction allowed to redirect the business opportunities onto a smaller number of companies, which emerged strengthened in a regenerated, relieved of its least competitive elements market.

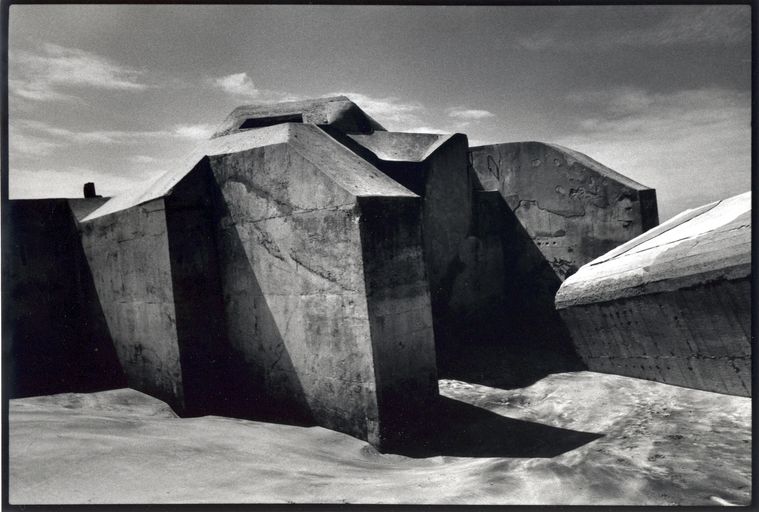

As Wehrmacht’s operations started to take a wrong turn on the Russian front, Hitler decided to focus on the western front and strengthen the Empire’s Atlantic coast defense line by building an exceptional network of fortifications from Holland to Spain: 8,000 casemates, an artillery battery every two kilometers, a continuous line of various works ranging from barbed wire to several meters thick concrete works. Albeit questionable from a defensive point of view, this monument to economic collaboration however played a decisive role in the development of France’s concrete industry. While craft businesses were at a standstill, watching their workforce being drafted in STO’s labor camps, larger companies were on the other hand eased into maintaining their activity. At first, the organization responsible for the building of the Atlantic Wall, Todt, only included German resources. But soon enough, German companies were, for convenience issues, encouraged to form partnerships with French companies. French construction sector thus suddenly boomed and reached a turnover of nearly 671 million francs in 1943 (for 16 million in 1941). Eighty percent of all French cement was then used solely for the Wall construction. Vichy government also used the boom for propaganda, as the drop in national unemployment rate went from one million unemployed in 1940 to only 10,000 people in 1943, as 300,000 French workers got mobilized on wall construction sites.

From 1942 onwards, the volume of construction sector, which had been reduced for about a decade since the 1929 crash, increased significantly. Implanted away from any military bombing targets, cement plants were running at full capacity, paving the way for the concrete industry’s unlimited development. The Atlantic wall created the unexpected economic miracle allowing French companies to return to activity and create profit. It is indeed the construction of those fortifications that allowed France to maintain a high-performance construction industry, fully-operational for reconstruction, while the said fortifications ironically became obsolete as soon as they were completed.

After the war, thirty percent of all cases handled by the National Interprofessional Purification Commission (CNIE) concerned construction companies. Considering that their motivations were more economic than ideological, those companies were most often given extenuating circumstances, and the condemnation of a few businessmen took care not to alter production chains. Time went by and, from mergers to acquisitions, technique acquired during this WWII business boom was fully adopted by the whole sector, while the bad reputation attached was left to rot in history’s shadows. Thus, ever since the war economy and reconstruction, reinforced concrete continues to dominate French construction. The business opportunities granted after the war as part of the Marshall Plan foreshadowed the formation of today’s big construction corporations, who now play a structural role in the country’s equipment, while maintaining close and interdependent relationships with local authorities.

These processes have observable long-term effects which naturally question public interest. What is the next step of this industry mutation process, with only three majors currently sharing all of France’s construction market? What is the long-term effect of this quasi-monopoly, that holds exclusive ownership of some technical resources?

This article was first published in issue 26 of “Tous urbains” magazine in June 2019.