The example of Detroit in the United States can be seen as a significant stage of degrowth and emerges as the major axis of a new urban paradigm. “Reanimate the ruins” was the topic of the 2014-launched competition aiming to pull the city out of both depression and recession. The French-designed winning project “Cross the plant” planned to transform the former Packard automobile production plant, which had been abandoned since 1987, into a high-intensity and evolutive urban center. The team’s strategy was to use a combination of social dynamics and economic strategies to recreate an active and attractive “urban piece”.

Detroit is indisputably one of the most emblematic of all shrinking cities. There, the crisis bears several faces. Home to Ford, Chrysler and General Motors, the “Motor City” is, in 1930, America’s fourth largest agglomeration in terms of population. Impressive record for a city mostly developed on the sole premise of automobile industrial growth. This prosperous first half of the 20th century saw the rise of several industrial buildings that now seem bitterly oversized – mainly because they were built on the scale of assembly lines, nowadays automatized. In 1950, its population reached its peak of 1.8 million inhabitants, before starting to inexorably decrease. The 1950s saw Detroit inhabitants and businesses alike preferably settling on the outskirts of the city, slowly transforming the urban landscape into the American ideal of downtown skyscrapers versus single-family houses in the closest suburbs. At the same time, the automobile industry started its slow decline. By 2012, Detroit’s metropolitan area was reaching a total population of roughly 4 million people, yet only 700,000 [1] lived in the city itself! 82% of those were African American and around 38% of them lived below the poverty line… Deindustrialization process inevitably led Detroit to face an urban crisis; while the subprime crisis of 2008 finally sped up the city’s decay by leaving many houses in ruins (when they were not deliberately set on fire by creditors to prevent squatters – or original inhabitants – from returning). The loss in both population and land revenue – property tax being at the core of American urban financial system – led the municipality into a true financial abyss, cutting down all public services up until 2013 when the heavily indebted city was finally placed under federal tutelage, a rare occurrence in the United States.

All governmental efforts to reverse population drop and poverty are sadly fueling the economic, political, social and ethnic heavy unbalance anchored within Detroit’s urban history and urbanism, and deepen the original inequalities dating back from the 1950s. Thus, offering a contrast of two worlds with a privilege population at its core, surrounded by a middle- and working-class population in the suburbs.With great resignation, the municipality accepted to hand Downtown and Midtown over to private real-estate investors, who now operate all sectors ranging from construction of vast office buildings to the management of public spaces or the leading of housing operations. As a result, and despite a real desire to create a diversified housing offer, it is clear that gentrification has taken hold of the central neighborhoods, largely occupied by the educated upper-class (mainly families and young professionals from outside) to the detriment of those who lived there before. In fact, the absence of real governance or financial levers from the public authorities leaves free rein to intense real-estate speculation and excludes poorer populations in need of low-cost housing. One could call it an urbanism of austerity, where the absence of planning is there justified by the hope of quickly favoring both attractiveness and real-estate value.

Outside the downtown area, we can observe a drastically different urban phenomenon: in these areas deeply affected by the economical crisis, it is the communities of residents themselves who, gradually and according to their needs, unite to tackle the issue of housing vacancies, the deterioration of public space, and the lack of city services.. It is a slow battle, led plot after plot according to the communities’ most urgent needs. Yet, it is indeed the communities who end up taking charge of education, social and solidarity activities, temporary or permanent development of public space, etc. With the support of the municipality and Detroit Future City – an independent structure working for community-based and experimentational development – empty plots are reoccupied, vegetated, afforested or cultivated [2]. Would this economic response from civil society be a viable path for positive urban planning and the implementation of new urban models?

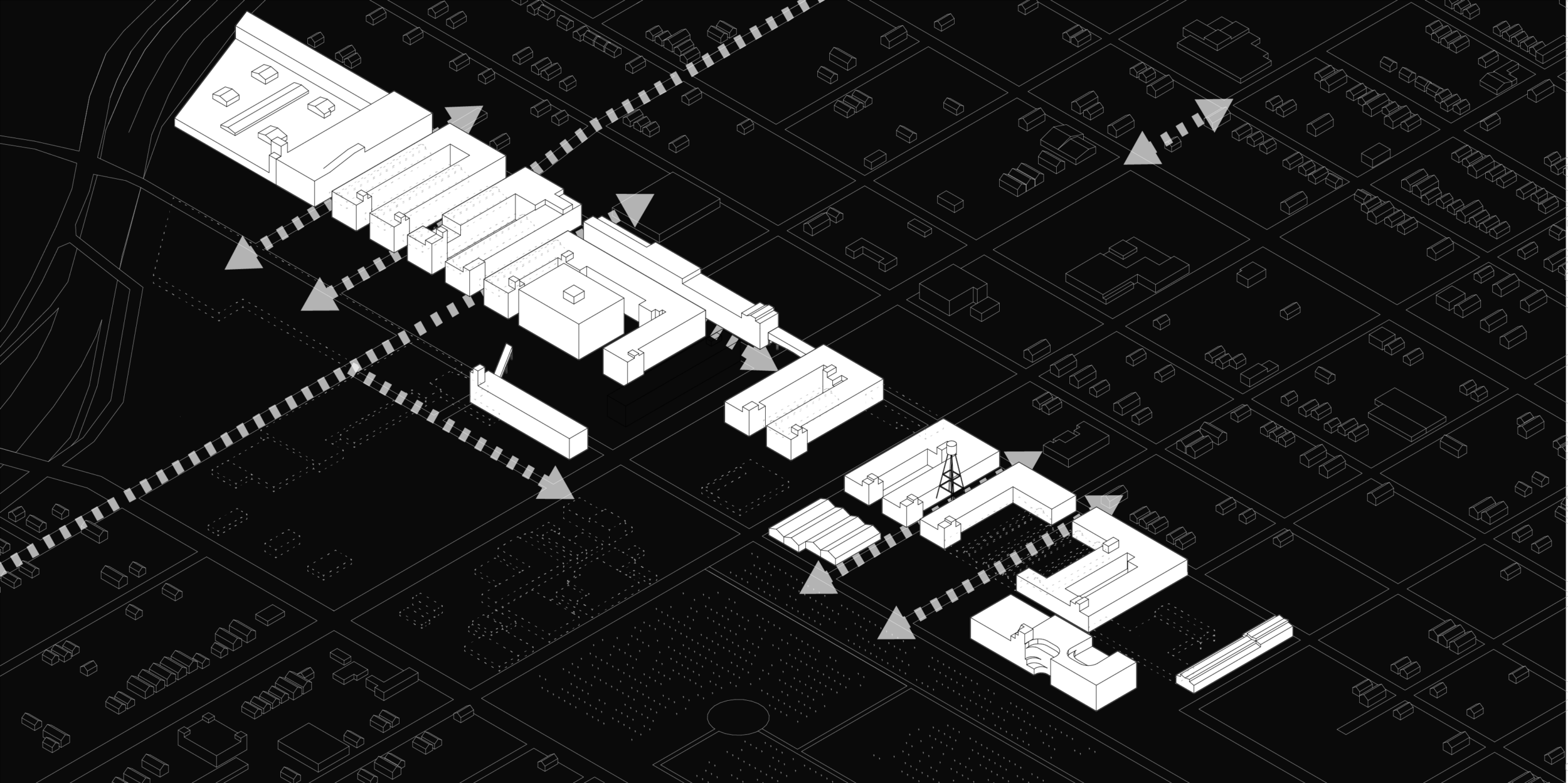

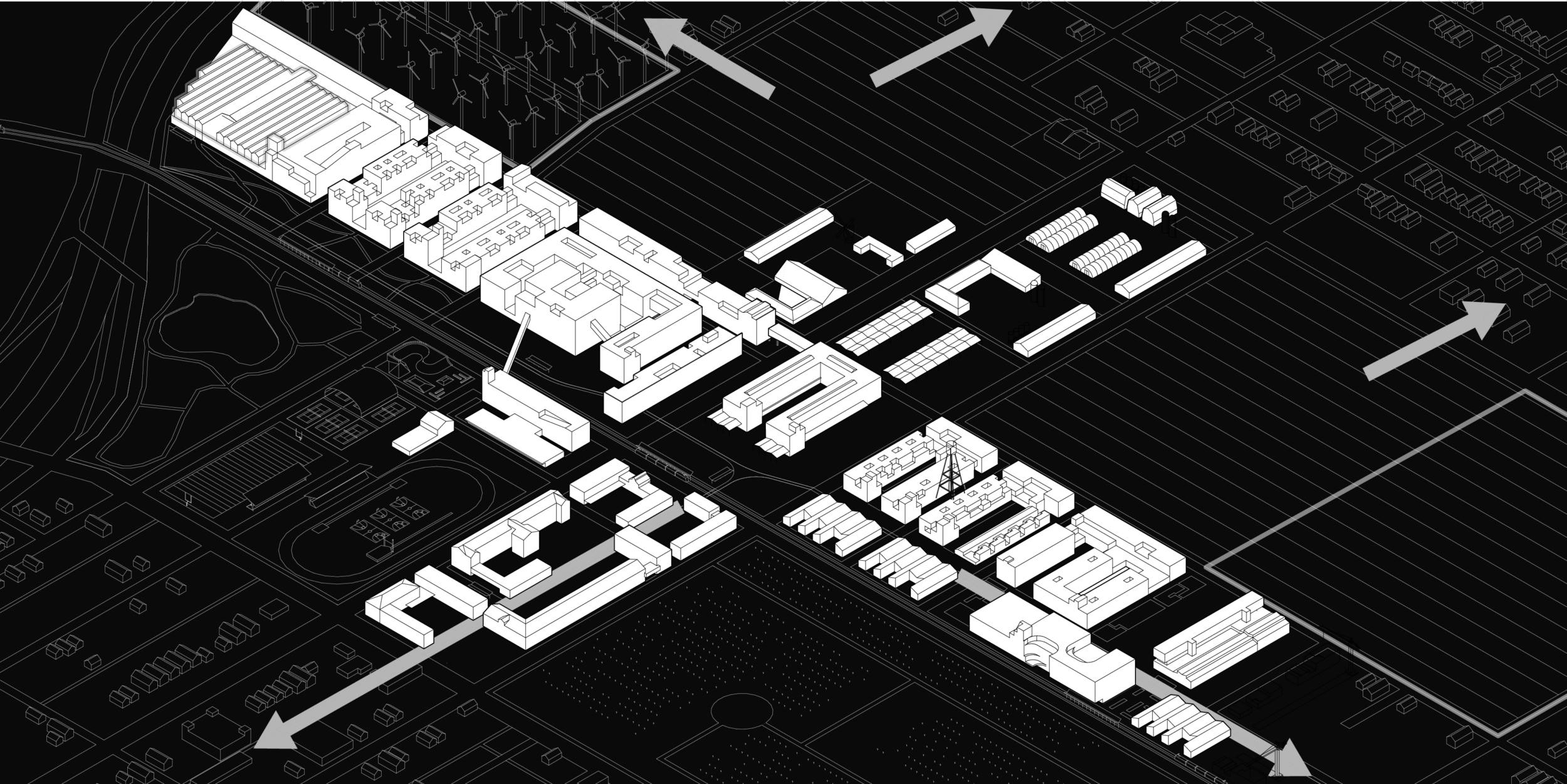

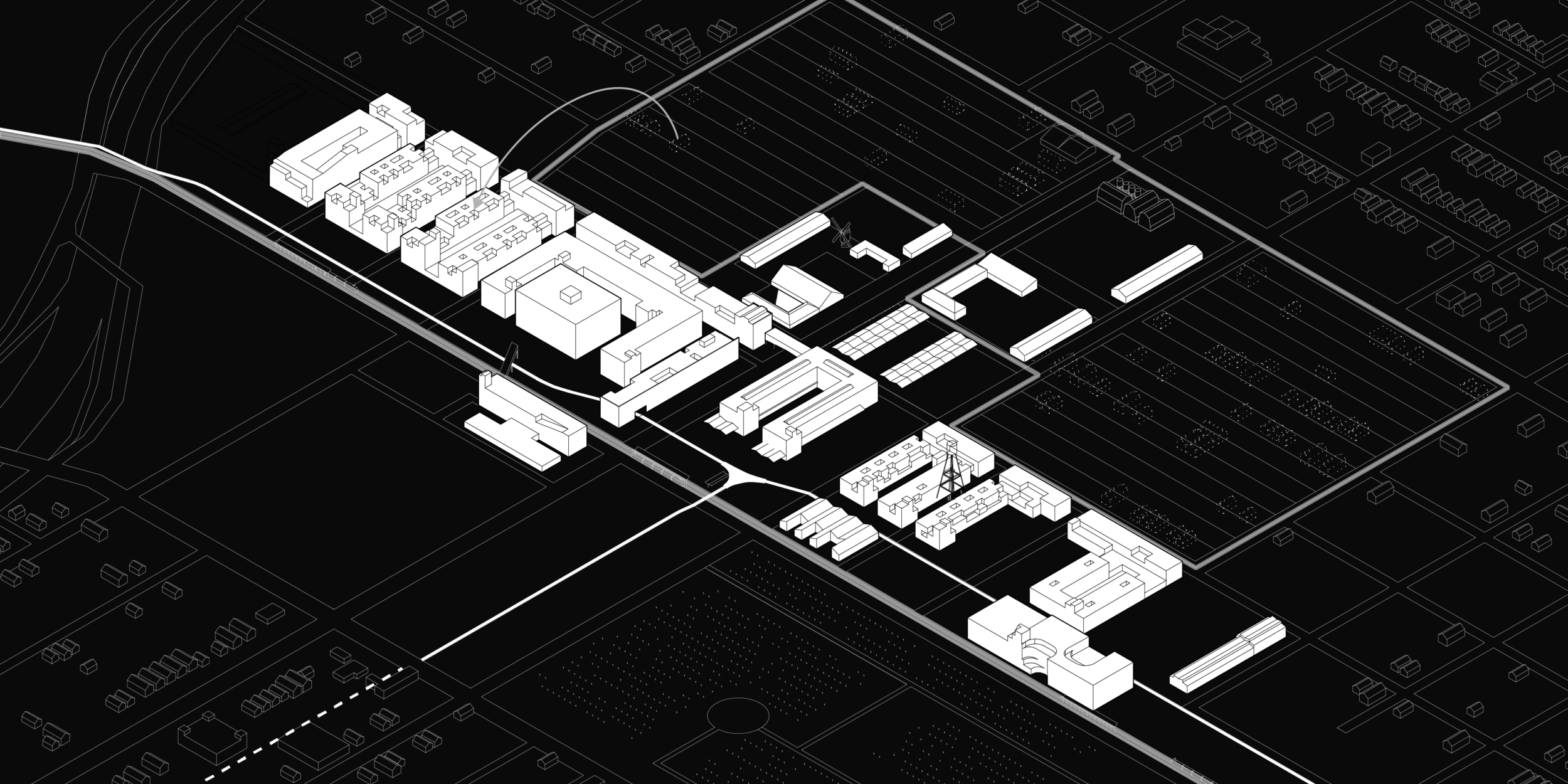

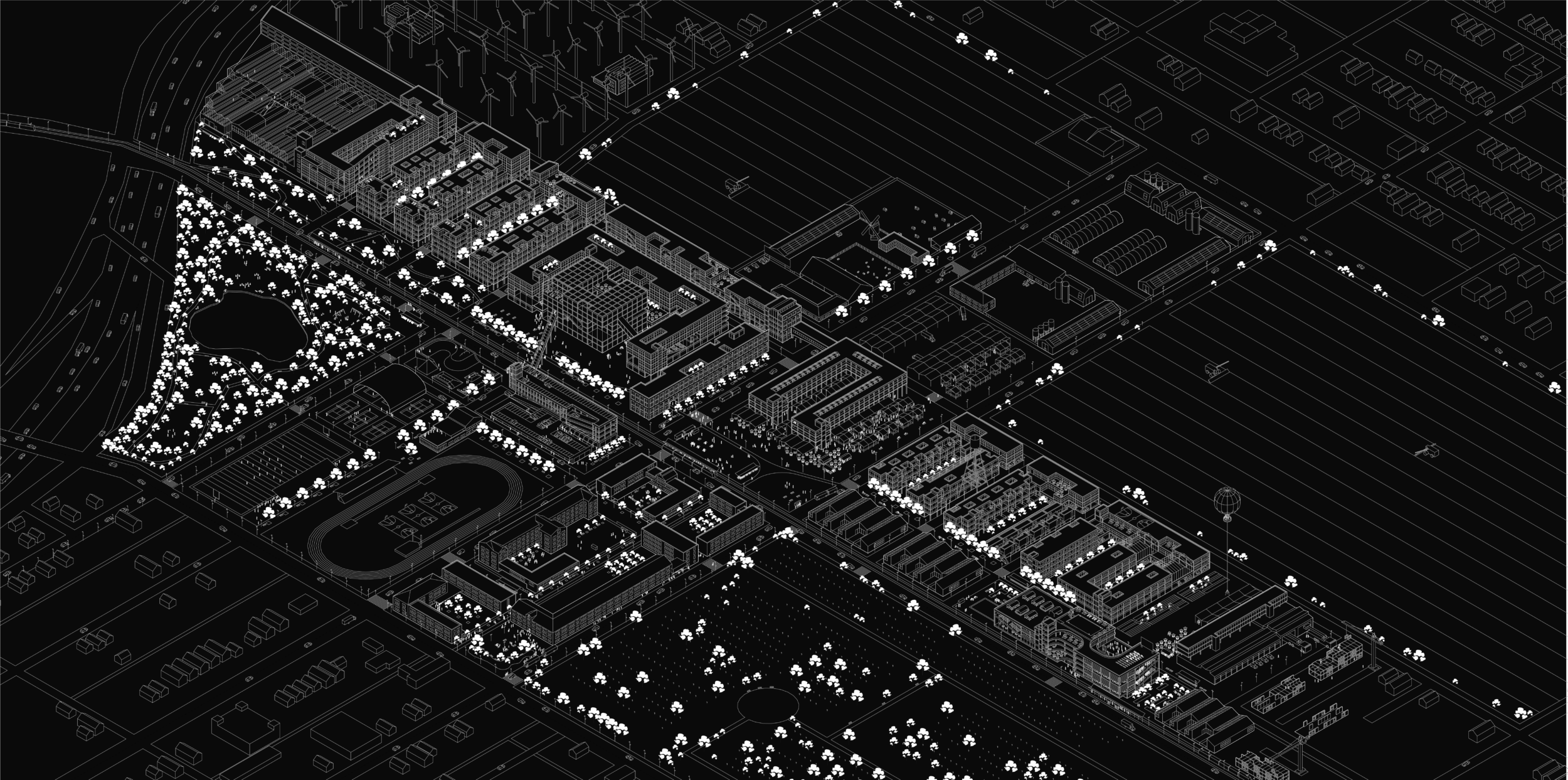

Phasing of the operation into 3 major sequences. Copyright Vincent Lavergne.

The case of the Packard plant

Up until its closing in 1956, the Packard Automotive Plant was an internationally-renowned luxury car production unit. The factory, whose multiple buildings had been designed starting 1910 by the architect Albert Kahn with the contribution of his engineer and specialist in reinforced concrete brother Julius, was among the first production sites to be installed in Detroit, yet also one of the first ones to close. The new owner rented out the various buildings to several companies until selling the whole – which covers some 32 hectares – in 1987 to Bioresource, a company owned by a businessman since known for repeated tax defaulted payment. After many twists and turns, a few half-illicit land occupations and many legal battles, the Packard plant was finally taken over by the City in 1998 with the intention of demolishing it, yet the magnitude of the task and the presence of asbestos got, at the time, underestimated. A year later, it was thus conveniently saved from destruction by Old Packard Plant Mortage Acquisition Corp (OPPMAC), created by…the new head of Bioresource.

With scandals and interference multiplying, the site has become an outlaw area where even firefighters were no longer entering, until justice decided to expropriate the renegade OPPMAC and auction the building in 2013. Today, the Packard Plant belongs to Arte Express Detroit – a real estate promotion company specialized in the revitalization of historic buildings. The undergoing development project includes tertiary and “cutting-edge” service programs, but excludes any form of housing or real social program.

Located seven kilometers northeast of Downtown, the Packard plant employed up to 40,000 employees and, once surrounded by fields, was quickly won over by urban growth before it went under the various industrial and economic crisis we previously evoked. Its site is thus representative of these neighborhoods once on the outskirts of suburbia, ending up being caught between two scales of construction. On one side the once dashing now ruined capitalistic monument of the Plant; on the other, large plots holding moderate to low density single-family housing, whose low-income population is unable or unwilling to leave.

The “Cross the Plant” project’s stake is to successfully transform the former one-kilometer-long industrial site into an active urban center. Copyright Vincent Lavergne

Farnsworth is still alive

West of the Packard Plant is the small Farnsworth neighborhood located in Poletown East, where Polish immigrants had settled in 1914, after the construction of the nearby Hamtramck enclave city now held by General Motors. The land division of this suburban territory, on the edge of both the city and vast agricultural land still reflects the very low-density of that time. As a matter of fact, if we compare Detroit’s 1905 plan to today’s, it is evident that the current subdivision of plots into small units was much less significant back then.However, the neighborhood was already oriented around the Trinity Cemetery’s vegetal cluster and limited by the same large railway and road infrastructures we can see today. Surprisingly enough, the degrowth process of Detroit seems here to result in a sort of a return to a prior state of land occupation, that of before any industrial embalming.

Farnsworth has had its share of desertification and crises. Yet, its success crowns the conviction and commitment of a teacher, Paul Weertz, who has been working relentlessly for years to keep the neighborhood away from decay. The man began renovating houses by himself while taking care to clear near-by abandoned plots. He also maintained his own vegetable garden and gradually moved towards a form of self-sufficiency. From there, his action develops as the community spirit strengthens. The 2008 crisis gave rise to one of the first citizen movements that proudly assumed its cultural transformation while undergoing a suffered economic mutation. Little by little, urban agriculture has become sustainable in Farnsworth, public facilities have been maintained or reopened, and public space keeps being maintained… albeit gentrification remaining relatively low. The federal state and the municipality showed support by giving land a stable status capable of resisting the pressure put by speculative real-estate markets. They also brought funding, allowing the promotion of a certain continuity between land-recovery actors, redevelopers and operators. Today, Farnsworth is described as a true citizen-based success story that serves the city and carries a new form of assumed urbanism.

New urban paradigm?

How can you articulate the diversity and the difference in attractiveness of different urban fabrics such as this ruined industrial cluster and this dynamic residential area? Will the location, image and architectural typology of the Packard Plant foreshadow a radical and speculative transformation, similar to Downtown’s and Midtown’s to the detriment of the nearby population?

The Packard Plant redevelopment project blossoms in 2014 when Parallel Projections, a company created by three young architects including New Yorker Kyle Beneventi, organized the international idea competition “Reanimate the ruins” about the site’s conversion, in order to contribute to “healing Detroit technologically, socially and aesthetically”. Among the jury was also a representative from Detroit Future City. Based on the solid post-and-beam structure that characterizes the rows of partially ruined Packard site buildings, our winning project “Cross the plant” (not realized) proposed an innovative transformation of the site into a proper urban center. Our proposal was based on the inner spatial qualities of the Plant’s medium-height buildings and the main transportation axes of Grand Boulevard, the railway tracks and Bellevue Street. The buildings in good condition are rehabilitated, while the irrecoverable structures are destroyed. New streets break the one-kilometer-long building of into several blocks on Concord Avenue. The site is also restored and reconnected to the city’s urban fabric by implementing a new tram line on the once-abandoned route that now connects the city’s revitalized airport to the Downtown and Midtown neighborhoods. Additional bus lines, bike paths, sidewalks and redeveloped public spaces help build up the site’s attractiveness, with offices, public equipment as well as housing designed with prefabricated elements adapting to the existing concrete structure.

In the scenario, one of the buildings is transformed into an automobile museum, while others accommodate housing and public services. Copyright Vincent Lavergne

To reinvest both the Packard perimeter and the surrounding land, our project advocates for a complete relocation process: residents near the factory are financially encouraged to sell their homes and move inside the Packard Plant’s new dwellings. The space thus freed up makes it possible to carry out large-scale reparcelling and develop agricultural production there. The planned facilities include schools, sports fields, a social center, a locally-sourced food supermarket, a cultural center whose architecture and layout emphasize the singular beauty of the ruins. The largest building is transformed into a museum dedicated to the automobile industry, its history and its prospects.

The Packard Plant was supposed to become a new urban life center that would develop and become more and more complex over time with the implementation of new public service installations. These actions aim to create new multifunctional plots as a proposed urban form for the site’s requalification and redevelopment.

Throughout the project, we sought to combine the interests of real-estate investors with those of residents. Indeed, connecting the Packard Plant to downtown actually means “expanding” the latter and thus favoring market-driven speculative dynamics that are not conducive to maintaining the original population in place. “Cross the plant” is, in that regard, a global proposal – from transportation structures to housing buildings and from neighborhood to city scale – which pushes the city towards a process of self-transformation while also creating new space for a rediscovered rurality. It leads a new path for studying the controlled decline of cities – or should we say the urban regrowth of the post-industrial city? – and thus vows to pave the way to a true innovative urban paradigm.

The piecemeal sale

Currently, the city of Detroit has not yet considered improving the public transit in this area, and is more focused on demolition projects rather than reconstructing and providing better public services. This lack of long-term vision and planning from the public authorities, who allow the owners to take the lead, remains problematic for the case of the Packard Plant. The site’s vast expanse continues to make it difficult for a single entity, whether public or private, to carry the project alone. Only a thoughtful and controlled division of the area into medium-sized blocks would have avoided all the twists and turns -or the current piecemeal sale- the site is currently going under; and it seems that without finding an appropriate scale for the Packard Plant to graft onto the surrounding blocks and multiplying programs, activities, populations… “making a city” will remain a utopia.

[1] 2017 Records show a number of 673 000 inhabitants.

[2] For more information on the recent redevelopment operations, see the documentary « USA: Detroit, la renaissance », directed by Laurent Cibien and Pascal Carcanade, 2018, 37 min.